- Home

- Carole DeSanti

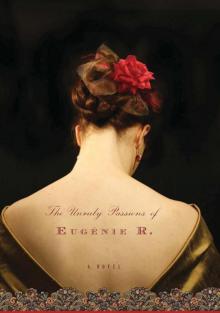

The Unruly Passions of Eugenie R. Page 2

The Unruly Passions of Eugenie R. Read online

Page 2

My seventeenth birthday had passed just after the New Year. We had celebrated it in Stephan’s bed—or rather his uncle’s bed, to which we had made profound claim—dining on brandy plums, foie d’oie, roast chicken; market cheeses, crusty white bread. The carpets were littered with corks and bones and plum stones and Bovary, its binding splayed over a mound past due for the wash. Stephan had tossed it there.

“In Paris, you know, girls your age are not allowed to read Bovary.”

“What do they read?”

“Works of moral improvement that encourage them to uphold the social order!”

He laughed and threw back the bedclothes. Drowsy and effervescent, I slipped into the warm furrow his body had left. The windows were fogged from the heat of the fire; Stephan shed his robe. Water slapped gently against the sides of the bath as he stepped in. The taste of foie d’oie and the musk of his flesh lingered on my tongue, a touch of salt; champagne tingled through my veins. Our sprig of Saint Nicholas mistletoe still dangled on the bedpost, its white berries now dried to husks. Outside, the gardens lay under a glittering sheen of frost, the last of the roses long gone; the lush foliage of the borders stripped of color. The day’s diminishing light fell through the diamond panes of mullioned glass.

“Little goose, wake up! It’s nearly nighttime.” My lover parted the bed curtain and stood clothed. He picked up Bovary, passing his fingertips along the spine. Emma, as I had left her, was bankrupt with dresses, running from lover to lover. I slipped beneath the sea of linen, awash in a strange irritation. Stephan lounged on the edge of the bed, picked up a knife from the litter on the carpet, and began peeling a winter apple. That knife drew a line between us, as he ran the blade across the fruit’s surface, flaying it of its rosy skin. Then he told me a story, better than Bovary because it was our own. It was set in Paris and there were parties, dances—masked balls in gardens. Ice skating on frozen lakes inside the city; fires with crackling wood and hot drinks with rum. Horse carriages along the streets, with bottles of champagne. We would fool them all, delight and convince them—who?—I did not ask.

He dropped the paring, an unbroken spiral, to the floor. Cut a thin, perfect slice to the core, a sliver like a new moon. An owl hooted, a gentle but worrying hoo-hoo, very near. Toast crumbs from our bed feast pressed uncomfortably into my flesh.

“So, we will be—married?” I ventured. We had discussed it on our long flight from my home province to the chateau—it was not so much a promise as simply an understanding, clear as the sky was blue, which it was, once we left the southwest’s clouds and smoke.

“But we must avoid Bovary at all costs, don’t you think? A stifling life, both of us miserable and bored.”

I giggled. “It wouldn’t be; you are nothing like Charles Bovary. A dull doctor.”

“I’d rather not find out if marriage transforms me, then.” Stephan assured me that Paris was nothing like a tiny, convention-bound provincial village; the capital was law unto itself. I hesitated—never having considered Tillac, the place I was born, in that light. I did not miss the odor of the goose pens, though.

“Why can’t we just stay here? The days will lengthen soon. The ice will melt and we can plant a kitchen garden.” Fingers in the dark soil newborn from the frost, sieving it to breadcrumb size, nestling tiny seeds—carrots, lettuces—tucking them in a moist, well-aired bed, and watching for the first pale green shoot. “I’d like to eat something besides foie d’oie. A radish.” Its taste fresh and sharp, like a slap of spring wind . . . “And if not married we should be engaged.” Stephan pulled himself up and gazed into my eyes, and with all the earnest belief that this slate-eyed scion—heir to difficulties I could only imagine—could muster, he summoned up what he could.

“I will be your protector. It is—you know, how things are arranged. In Paris.” And then the heavy beat of wings and a flustered scuffling above our heads, and another wavering cry.

The next morning I left for the train with the sheaf of bank notes that Stephan had laid out on the library escritoire, a cache of borrowed gowns in my traveling bag, and visions of blue silk dresses. (“Paris skirts are very wide.”) The bolt of fabric, another New Year’s gift, did not fit into my luggage; we stood awkward, the cloth between us, and tears threatening. Finally Stephan promised to bring it with him when he came. “Our first stop shall be the dressmaker,” he said, planting a kiss on my brow; rather more like a father, or an elder brother, and in fact—now that I considered it—in the very place that had been smacked and was now a bruise.

Flashing, blue-fledged hue of a teal; the last of the wild-breeding ducks to appear, fast and wary of hunters in the ponds and rain-filled ruts of southern France . . . the fowl’s colored feathers appear in December, briefly against his mottled brown. After that, he molts, flightless.

In this world, a girl like me, brought up with her knees regularly pressed to the flagstones, the church’s incense mingled with the pine-needle scent of the forest floor—the oldest daughter of ambitious parents—such a girl did not dare her destiny, her parentage, everything—and lose. The consequences of would be so catastrophic, so utterly beyond the imagination—even a rich, rebellious one like my own—that they did not, even for a moment, enter my waking thoughts. But I had begun, again, to dream.

I stepped past a used-book stall, its offerings stacked like slices of bread, moldy at the crust. English hymnals, cookery books, cheap novels, and Bovary in two volumes, bound together with a band advertising it as BANNED! CENSORED! Somewhere in those pages Emma was in midflight, but I had lost my appetite for her travails.

The streets spiraled inward and tightened toward Notre Dame and the city’s beating heart; peddlers hawked chestnuts and tobacco, coffee and thread, paper and dried fishes, songbirds and window glass. Pyramids of dusty wine bottles. Passing the shops I saw signs of my lover everywhere, tying invisible strings between Stephan and what he loved: chestnuts in honey syrup; racked bottles in a wine shop; in a patisserie window, a tower of raspberry tarts. These stood out like flags, those of the nation to which I belonged. We had brought home just such oranges in a string bag; those brandied apricots in a bottle.

Now, choppy January currents ruffled the gray waters of the Seine. I nibbled chestnuts and sipped at another coffee, bitterer than the first. Nearby a gang of workers in blue cottes were packing up their spades and turning their horses. The wind picked up; I shivered under a paisley cashmere, borrowed warmth. Blisters already chafed under my boots, very nice kid ones that buttoned up the side, barely worn, recently white.

Back at the Hôtel Tivoli,with no knife to cut a loaf of bread, peel an apple, or pare a portion of sausage and cheese so as not to have to bite off chunks with my teeth like an animal—with no cup nor table at which to drink from it, I took out a thin sheet of paper from a fresh, new stationer’s package. With a sharp-nibbed pen atop the shaky candle stand, I wrote, Dear Stephan, I saw the Seine today, and a cart full of Seville oranges . . .

In the wavery, pitted mirror of number 12 was a young woman, myself, certainly—dark hair and pale skin; not so badly off in her borrowed finery. The soft hair, the curve of cheek and shine of my eyes—violet-gray (a shade off Stephan’s)—were as they had always been; but the calluses and rough edges of a faraway province had been buffed away in recent months by some chemistry of love and unaccustomed kinds of bathing. Staring, I willed blindness on myself; insistent, willful ignorance. The holes in the story I told myself, pinpricks of truth like the quills sticking through the mattress ticking of number 12, would become rips as long as those my petticoats would show in a few weeks’ time. But doubt, smaller than a tiny seed, sown somewhere deep—had not yet sent its root tendril; had no thought, yet, of unfurling its leaf.

2. The Trap

ANY PAINTER’S DAUGHTER (and I was one, of course) knows that a picture requires constancy of place, climate, care, and conditions to maintain and protect its surface, to prevent its color from cracking and falling away. But to apply these

principles to life—to shield it from the ebb and flow, the shifting and carrying on, the wearing away—this knowledge my mother, Berthe, did not pass on. She never explained what substance hours and days are made of; nor how time wears on the mind when one is in love. How a lover, once present, becomes a story you tell yourself—although I believe that she knew these things.

It was soon clear that the Tivoli was not a pleasant place to spend time. For one, the clerk who frequently replaced Madame at the desk pretended not to notice my presence, while I knew that he had. When he appeared I lowered my head as the sheep to the dog. Only once in the corridors had I seen a guest anything like myself—a blonde, pale-browed girl in indiscriminate garb—“neither fish nor fowl,” as Maman would say, and not to flatter. The girl appeared only briefly; when I looked for her again she was gone. With my diminishing clutch of bank notes the initial charms of the capital were already, by the third day, wearing thin. Dingy swells of working girls coming and going, knots of beggars in the shadows of Notre Dame, the tides of workmen with their spades; and unapproachably extravagant shops on the rue de la Paix—all were becoming tainted with vinegar, like wine going off. Omnibuses passed up and down the rue Saint-Lazare while I walked endlessly and without destination in shoes not meant for cobbles; in a veil that trapped the street dirt in my eyes. (My old sabots, woolen dress, and thick winter cloak would have stood up better to the conditions, but those things had vanished as though they never were.)

By the time dusk fell, the working girls in sparrow brown and the cinched and silk-clad shoppers alike disappeared behind gates and doors, the battered clang and the turn of latchkeys echoing behind them. I hurried to make it back to the hotel by curfew, with no idea of what would happen if I was late—would I be stopped by a gray-coated police officer, like those patrolling the perimeter of the Luxembourg Gardens? Scolded by Madame, thrown in prison, taken before a court? So every evening I returned helplessly to dwindling provisions laid in for this siege of waiting.

Across the street from the Tivoli, the crinoline shop’s empty bells swayed, knocking dully against one another in the sharp gusts.

On day five, the baker on the farther end of the Passage Tivoli cut bread into squares and put the samples out in a basket. A woman at the counter (wrapped in a blue shawl too good for the dress underneath) moved her hand cautiously from basket to mouth and back again, slowly moving her jaw as though trying to make the chewing movements small and invisible. Out of kindness, the baker had turned his back.

And now I missed Stephan terribly. No response had come to four nights of notepaper beset with inky, faithful marks and envelopes stamped boldly with the hotel’s address. Each morning, Madame sorted letters on the mahogany desk—her usual method was to extract some few and mysteriously disappear with them while I stared at the newspapers and waited for the shadow indicating her return. Eventually she proceeded to sort the mail into pigeonholes by guestroom, her bulk eclipsing the whole project. From no place in the lobby was it possible to discern whether an envelope had found its way into pigeonhole number 12, and so I was ignorant of my fate until the whole abysmal task was complete. Then, empty-handed and with a hole in my heart, I went out to walk.

Around the supper hour the lamps flared to life; my stomach pinged, and the trousered portion of the citizenry and those on their arms proceeded to conviviality and dinner. I lingered before a chalked board in front of the restaurant Trap a short way up the rue Saint-Lazare.

Potage aux Croutons

Spécialité du Jour: Fricandeau

Potage de Fantasie

Bouilli Ordinaire

Dessert: Tartes Sucrées

The parted curtains exhaled warmth and the scent of mussels and garlic; the chink of cutlery and the music of glassware floated out to the street. On one of these evenings, the barman appeared with a cloth flung over his shoulder.

“The soupe du jour is good tonight, the boeuf à la mode like butter. And some very nice oysters grilled in their shells.” He nodded at a pile of bricks and rubble. “They won’t cease over there, will they? Pulling people’s houses down around their ears. The dust today was terrible. Why don’t you come in? The wolves are kind at the Trap.” When he squinted, creases feathered around his eyes, but he was not an old man.

But I shook my head and hurried back up the Passage.

By seven on the Friday of my first week in Paris, I was pacing my room and rationing candle ends—cheap, fast-burning tapers bought from a sundries shop. A bottle of spot remover, cheap stationery and broken pen nibs, and the remains of my own dinner, chocolate crumbs wrapped in paper, were crowded on the small candle stand. Like the worn-out carpet, flat pillows, and meager walls, life itself had thinned, and I dwelt on what, in the recent months with Stephan, had been thick and fat: rugs and rose petals; framed pictures; pillows and featherbeds that were fluffed and tucked into place every morning. Cream in coffee, the glistening edge of the meat. Hours marked by chimes, heavy and honey-laden, like dusty bottles of Sauternes in a cellar; not least, Stephan’s presence, around which I could wind my self and soul. It had begun to seem like a dream as I flopped onto the flat, prickly mattress and faced the ceiling cracks, seeking the connection between these forking lines in the plaster and the events that had led me to stare at them now. A plausible story to wrap around my situation. Smuggled up from the lobby was the evening’s entertainment, a copy of Paris Illustré, with its society events, brief anecdotes, and gossip.

From this source I learned that on the contract day of her marriage, Mademoiselle de Gr—’s engagement gifts from her equally aristocratic fiancé, Monsieur de T—, included antique lace, an ivory fan, a candy box inlaid with semiprecious stones, two cashmere shawls, and a purse of gold coins for charity . . . Also, that residents of the rue Saint-Jacques would miss a familiar figure, a tall gray-clad lady who had wandered the neighborhood carrying a shredded umbrella and a zinc pail into which tourists dropped coins. She had been found dead in her lodgings (asphyxiation by fumes from a coal stove, a suicide). She was in such poverty that she made her bed in a soap crate, but in a metal box inside her chimneypiece was a fortune in bank notes, along with a letter asking that the funds be used to fly her to the moon. Her one-time love had gone there already, she wrote—a soap magnate who had lost his fortune . . . And that it was now possible to find twenty-nine varieties of mustard in the capital, among them Red, Powdered, Flavored with Garlic, with Capers, or Anchovies; with Lemon, Tarragon, Fines Herbes. Truffled, prepared for the empress in honor of a marquise; Tomato, Black, Green, Roman, and “For the Health”; this last, though prized as a condiment, was also known for the treatment of—

Next to my ear I heard a sighing sizzle, and the last of the candle ends snuffed out: then, silence. In the darkness, afterimages of the newsprint floated.

EMPEROR EMPLOYS GAS IN PALACES, DISAPPROVES OF ELECTRICAL LIGHTING INDOORS.

CONSTRUCTION WORK ON THE RUE DE RIVOLI TO PROCEED AT NIGHT: FEMALE VIEWERS, ESPECIALLY FOREIGN TOURISTS, WISE TO BE ESCORTED.

RENTS SOAR: LODGINGS IN PARIS IN SHORT SUPPLY. ARTISTS AND STUDENTS REVOLT.

PLAGUES OF RATS AND LICE.

GREATER NUMBERS SEEN IN THE UNRULY FEMALE POPULATION; MORALS BRIGADE TO ADD OFFICERS.

EMPRESS TO HOLD USUAL WINTER ENTERTAINMENTS.

What I had gleaned, these emptied-out evenings, was that an intricate web of law and social relations spread out over the capital like a giant net. From cradle cap to mourning veil, fashion, rumor, and gossip suggested what was good and bad, frowned on or approved. Columns and anecdotes hinted, critiqued, and applauded like great crowds pointing and chattering on every corner, making oblique references to the Code Civil. I knew about the Code Napoleon and how it had abolished a piecework of old feudal laws and practices, organized the legal system—but I wished that the rules of Paris—“law unto itself!”—had been spelled out. (Of course, if they had I would have been confronted with the fact that the Code Civil had also been written to organize out of

society exactly the behavior that had thus far characterized my path—that is, passionate flight and a love affair with a man not my social equal—though of course, this was not how I viewed it at the time.) Instead, I could draw my conclusions only from the mysterious rules about hotel rooms, reports of old women who slept in soap crates, and the information that a poor girl whose virtue had been compromised might stick her arm full of darning needles and find a career as a hysteric at La Salpêtrière.

If Stephan were here we would have discussed it all, and he would have laughed and said that neither love nor money should drive you mad. But—where was Stephan? Why had he not arrived? I was about as equipped to manage Paris alone as to fly to the moon myself. A queasy wash of anxiety swung my feet to the floor.

Downstairs, the desk was unattended and the lobby empty but for a single man wearing a pince-nez. He glanced up from his papers, frowning as I headed past without looking to the left or right; and the hotel door swung wildly open, gale-force winds seizing it. The latch fell to; a gust caught my skirts at the mouth of the Passage.

The Trap’s draperies billowed with a moist, fragrant breeze. At this hour, the early crowd had gone and had been replaced by a loud, convivial group. A hundred pairs of eyes flew in my direction and lit like beetles, as waiters in blue aprons carried zinc trays aloft, unloaded plates of food, uncorked bottles, poured, and bent to hear their customers over the din.

With a gesture of pleased surprise, the barman (whose name I learned was Claude) settled me at a small table in a corner. I did not know whether to remove my hat and gloves or where to look, so I just stared at the bread and butter, served on a saucer. The butter was pressed with the letters REST TRAP. A carafe appeared.

The Unruly Passions of Eugenie R.

The Unruly Passions of Eugenie R.