- Home

- Carole DeSanti

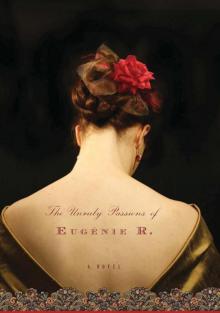

The Unruly Passions of Eugenie R.

The Unruly Passions of Eugenie R. Read online

Table of Contents

Title Page

Table of Contents

Copyright

Dedication

Epigraph

Prologue

BOOK I: Betrayal

1. To Paris, 1861

2. The Trap

3. Chasseloup

4. A Present Cure

5. La Lune

BOOK II: An Unknown Girl

6. Deux Soeurs

7. The Point of the Hook

8. Jolie

9. Salon News

10. L’Absinthe

11. Rue Serpente

12. An Arrival

13. The Garden

14. Tour d’Abandon

BOOK III: Gallantry

15. A Dinner Party

16. The Marchande

17. Contraband

18. Waters of Paris

19. Recherche de la Paternité

20. An Ink-Stained Hand

BOOK IV: Debacle

21. Declaration

22. Crise

23. Debauch

24. Surrounded

25. Fête de Noël

26. Bombardment

BOOK V: Degrees of Justice

27. Surrender

28. Between Paris and Versailles

29. Correspondence

30. Rue d’Enfer

31. Grotto

32. Auch

33. Indemnity

France, 1848–1871

Glossary

Acknowledgments

Copyright © 2012 by Carole DeSanti

All rights reserved

For information about permission to reproduce selections from this book, write to Permissions, Houghton Mifflin Harcourt Publishing Company, 215 Park Avenue South, New York, New York 10003.

www.hmhbooks.com

The Library of Congress has cataloged the print edition as follows:

DeSanti, Carole. The unruly passions of Eugénie R. / Carole DeSanti. p. cm.

ISBN 978-0-547-55309-2

1. Self-realization in women—Fiction. 2. France—History—Second Empire, 1852–1870—Fiction. I. Title.

PS3604.E7549U57 2012

813'.6—dc22 2011016540

eISBN 978-0-547-66120-9

V2.0512

To my friends

The logic of passion is insistent.

—STENDHAL

Prologue

Paris, May 1871

This train, the Aurore, is a night train, headed south-southwest. A drape is secured across the window and behind it is a deep, quiet blackness. The compartment is a box with brass locks, rough-napped tapestry, and some silk fringe; fitted with a lamp. Here, one can remove one’s gloves, take the knife from the boot; perhaps find again the textures of things, or one’s own thoughts. Between one place and another, at last neither here nor there. It is a respite, a still rush of night air. Behind us: the roar of a city on the brink of burning.

An hour ago we stopped for dinner just outside the capital, at a café counter in a station where the French tricolor flag still flew, and it was strange to see it in place of the Commune’s red, the defiant banners and colorful rags that had cropped up across the capital like spring poppies after a long winter.

We had a hasty meal, and then the entire body of passengers (Prussian officers included) climbed a low rise to see what we could. Whether, on the horizon, a dull red pyre lit the evening sky. Someone had a telescope, and silently, among strangers, we passed it from hand to hand. From this distance, no sign. The Prussians stood silent. They must certainly be marveling at a Paris again under siege, on the heels of what came before. If Paris burns, it will be the second time in my life that I have left fires behind, flames that laid waste to all I had known.

No sound but shuffling footsteps as we head back to the train.

Because I was a girl, and am now a woman, I have dreamed, some nights. Dreams do their best to reset the soul, but it is heavy work. Dawn, or noon, or whenever it is one pushes back the bed linens, brings the pressing needs of the day. Those who do not dream, or do not remember, are able with confidence to say, “I think, and so I am,” like the philosophers. I might once have said, “I love, and so I am,” and then, love was lost to me along with a thousand other things.

. . . How does a woman learn to doubt herself? When does it happen, and why? Is it in her blood and bones from birth, does her mother nurse her on it? Or is the alphabet learned later, then syllable by syllable a secret language between mind and heart, an argument between lovers? A night full of tears; by dawn, a heart gnawed to pieces. Ah, but it conjures itself to life, doubt. Preys on the sleeping; is the infection of everything touched.

Sometimes it seems that she cannot answer a single question about her life. Why has it been thus? How did it come to be what it is? And how does she begin to speak when all that has been understood has made any story too difficult to tell, when what is truly desired is so far from possibility—when she has made herself cynical, and before that, only guessed at what she knew? One’s story is made of gulfs and gaps; lies and arguments; the rise and fall of voices behind walls, placards pasted up onto walls at night, torn down in a fury and replaced. And then too—she has spent the days and weeks and years . . . in giving way. When, at what hidden moment, was the choice made; and what, in the end, did it yield?

I want to wake after the night’s rocking journey south to be dazzled by old white stone, the sunlight of late spring on the countryside where I was born. A relaxation of vision, a widening, finally, of the slits my eyes have become. Years pass, and one does not remember what might lie beyond the Paris walls. If the train window’s dark reflection could be lifted like a shade, would there be old walls, spreading oaks, the arches and spires of villages? Or are we yet too near the city, its slaughtering yards and rubble heaps, places where the night soil is dumped and the capital’s detritus is hauled to be picked over by ravens and urchins. Where the old women drag themselves, one-time boulevard girls rattling like stray stones. The grand cocotte who didn’t safeguard her hoard when she might have, and now sews sandbags for the Commune’s street barricades or serves the forts. All of a woman’s appetites become fiercer as she drives herself to ruin—I have seen it a thousand times.

Underneath my ribs, heat flickers—a feeling secured by whalebones and laces but nevertheless a hot, tight orb of—what?—rises and smolders in my throat.

As I boarded, a group of off-duty soldiers staggered through the aisles—French government troops stationed outside Paris, now encroaching on the Commune’s barricades and as ill-behaved as they were rumored to be. Searching out contraband, they said—evidence of insurgency—but they rifled through hand baggage, pulled cases off the racks, laughing and joking. Hunger rose from their bodies like the reek of cheap brandy. But I have knives in my eyes now, as well as in my boot; and I swayed through the cars unscathed, pressing my skirts through the narrow aisles.

I am in first class with the Prussians, but the lock is secure and I have no business with them. How I arrived here—in this compartment of blood, doubt, and collusion, all tacked together with elegant railway fittings and the black brocade of my going-away coat—is a question even I who lived it must ask. The Aurore’s whistle howls; we stop; then slowly pull out of an unlit station. Now we are well beyond the girdling Paris walls, the stones and mortar that Parisians call the enceinte.

Another train, another time. A girl, myself—a stranger now— one who took it upon herself to dare her destiny, and lost. I close my eyes against the roaring.

Horridas nostrae mentis purga tenebras.

Cleanse us of the horrible darknesses of our minds.

BOOK I: Betrayal

/> All that I have not dared say aloud,

I am going to set down on paper.

—Mogador, Memoirs

1. To Paris, 1861

THE TRAIN, NEARLY EMPTY when I boarded, had filled. La Loupe, Chartres, Rambouillet, Versailles—each station a fresh roar of voices, a jostling of shoulders and parcels and luggage. The car smelled of damp wool and iron, musky sweat and sour bodies; the windows were grimy with soot and dusk. In the seat next to me, empty an hour ago, was a stranger wearing the crumbs of his dinner—bread and Camembert. Once inside the Porte Maillot the carriage halted suddenly, went black for an instant of silence, a gasping intake of breath: “Next, Saint-Lazare!” We shuddered forward. I squeezed shut my eyes, wishing it all away? And abruptly smacked my head against the rail on the seat ahead, bone against iron; a wave of dizziness and emotion— Wait, turn back the clock, is it all a terrible mistake? A charred, acrid odor.

“PARIS!”

“They’ll be unloading us directly from the station to the hospital wards soon enough,” muttered the stranger, brushing crumbs off his waistcoat. “Just drop us off at La Salpêtrière!”

Paris. My aching brow. The bump was already beginning to swell into an egg.

***

“ . . . A hat, you goose—gloves,” Stephan had said, thrusting into my hands these unfamiliar items, companions to the soft silk of the dress I was wearing. “You can’t go about Paris bare-fisted and naked above the neck!” Now the veil’s decorative flecks swarmed before my eyes, an irritating nest of spots.

In the cab, scents of horse and leather, musky cologne in the chilly air; my breath misting the window. Sharp, rolling turn down an ancient alley with walls close enough to touch. A stairway too steep to climb, cut into stone; rusted iron loops for handholds and strips of cloth on a blackened beam for a door. I hung hard to a strap as the cab took a steep, winding descent.

“Passage Tivoli, rue Saint-Lazare!” came the shout, and I reached for my handbag. Fat, stuffed to bursting, the flimsy thing, but I counted out every last sou of the fare. The driver threw a curse behind me; I flushed hot under my veil. In my limited experience of travel, Stephan had paid, and undoubtedly tipped, the cabmen. Before that, it was the rutted market road to Mirande on the back of a mule, or we traveled on foot, and not very far.

Dusk had fallen. A double archway led to an arcade divided from the road by a gutter; suspended lanterns swayed above, with illuminated letters: HôTELS: TIVOLI, NO. 1; LISIEUX, NO. 2; VAUCLUSE, NO. 3. Every surface was plastered with placards and signs—generations of ruined broadsheets and framed notices for SALONS. CHAMBRES. CABINETS. Gaslit signs, lozenge-shaped, glowed above the hotel entrances, and a dubious gust scattered debris into a corner. Stephan had said that rooms in Paris were in short supply.

The Tivoli was nearest, and from behind the desk, Madame evaluated the scrap of black velvet on my head and its drag of veil; ran her eye over my smooth, strangled fingers clutching the strings of my handbag. Her shawl had a fringe of jet beads that clicked like a patter of rain, or Maman’s rosary when she tackled her penitence after months of neglect.

Silently, the required envelope crossed the counter, white against the pitted mahogany. Its edge was sharp, unsullied as fresh linen; the seal, red wax like a drop of blood, once hot and now congealed. I had laughed, the afternoon Stephan dipped his pen, finished, and dusted the page. We weren’t drinking champagne then, but tingling bubbles were still in our noses. “You’ll see how things are done in Paris!”

Madame slipped a knife under the wax and, with great and slow deliberation, unfolded the document inside, a thick, milky sheet. Her eyes narrowed and her gaze slipped over the page; then from the page to me and back again—cataloguing qualities unknown, the way my cousin cast his eye over the beam of a measuring scale as he slit open the bellies of the ducks and geese to weigh their livers for foie de canard, foie d’oie. Now, Madame’s eyes narrowed again with an opinion, the kind that is a known truth to the rest of the world. I had an impulse to turn and flee—but where?

“Haussmann is nearly on our doorstep with the tear-down boys,” she said finally, with a solicitude purchased, perhaps, by Stephan’s pen. “There’s not a room left on the Passage, but you’re lucky tonight, Mademoiselle Rigault. Yes? Very well then.” She slid the envelope back across the desk; now it showed a pinkish stain where the wax had been. “Ladies’ curfew at seven, sharp. No gentlemen above stairs. We have no improprieties here.” She gave me another beakish, penetrating look. “Candles twenty sous, gas is not piped all the way up.” Outside, from the bar à vin across the Passage, came shouts and drunken, echoing laughter.

My throat ached; the lump on my brow throbbed; my belly gave a hollow stab and a rush of heat rose behind my eyes . . . Paris. City of light, center of the World. Of civilization; of art. It took several matches, cheap and smoldering, to ignite a taper that revealed the attributes of room 12 atop an interminable stair: a scrap of carpet worn down to the threads, walls spidered with cracks, and a sagging mattress on an iron bedstead. A wooden chair, a candle stand. Freezing, dusty with neglect; the very walls closing in with a reproach.

I wedged the back of the chair under the knob. Then after a while, lay stiffly on top of the bedcovers in my street clothes and under my cloak, listening to my heart pound and the blood surge in my ears; crashes and yelps from the alley below. Cold seeped up through the floorboards.

Of all the damp gloom and dusky shades I had so far encountered, the void next to me was the most disconcerting and lonely of all. But Stephan would know, as well as I, this gaping emptiness; my lover would be feeling my absence just as I felt his. Yes, I had gambled; exchanged all that had defined me in the world—a rustic life in a distant province (where anyone who had ever been to the capital at all was called a Parisien for life)—the rutted road and antique habits of church and village, the goose pens, the obligations of a daughter—for Stephan’s kisses and his promises, murmured like silk to my neck and imprinted on every part of me, stamped into the wax of my being. Yes, I had contoured my life to his since Saint Martin’s Day last November, with not much to show for it but a promise and some borrowed finery against the January winds—but still.

“Don’t doubt me, Eugénie,” he had said. “Doubt, you know, is contagious.”

The last echo before I drifted under seemed to be the voice of my mother, Berthe, mocking behind my ear . . . You think your eggs are on the fire when only the shells are left . . . ! An old country saying, never-turn-your-back. Maman felt closer, in that instant, than Stephan, though I had left her farther behind. And in the moment of collision between what I had imagined and the clamoring consequences of my real actions came the ache of foreknowledge, like the bump on my head, and the simultaneous etherizing of it deep within.

I woke to the sound of church bells; insistent, unstopping, pulling me from the shallow marooning shoals of a dream. Dirty light filtered in through the window; a wafer of ice lay on top of the water in the pitcher. Paris. Blackened stub of wick in a pool of wax; an aching head and skirts pulled up and rumpled as though I had been ravished by something unseen in the night. I reached up gingerly, felt the bump above my eyebrow, glanced toward the door. The chair was in place. Splash of icy water, skirts pressed smooth with the palms of my hands. No maid, no Léonie; no iron nor fire to warm it; certainly no pot on a silver tray outside the door of number 12.

From below, the dim clink and clatter of crockery held out the promise of hot coffee, at least, so I followed the sounds down to a dull, high-windowed room. Four men in coats and cravats pushed back their chairs; and a kitchen door exhaled a cloud of steam and the odor of spent coffee grounds. A sullen boy scraped down pink tablecloths, steering around bud vases containing fabric flowers, their stems stickily coiled with green tape. Madame had said nothing about breakfast. Was it included with the price of a room?

Over the coming days, I would learn that the help spoke no French; nor did most of the guests. As unaccompanied ladies never

set foot there, my appearance on that morning set off a ripple of glances that sent me slinking out to a street cart, an old woman with a coffee urn, and a tin ladle meant for workmen. She too looked fisheyed at my gloves and hat as the wind luffed up. A strangled giggle rose in my nose and I tossed back the bitter stuff. If Stephan were here, it would all be a terrific joke—all of this unfamiliarity would disappear in a puff of smoke. Meanwhile, I must make the best of it. With the black brew in my hollow guts, I fished out my Nouveau Plan de la Ville de Paris 1860, with its indigo-marbled covers. My key to the capital.

By hard frost of that year—now past—the goose-girl from a tiny village hugging the Pyrenees had tasted defiance, and with it what she found she preferred: afternoons in a library sprawled on a carpet thick with Turkish flowers; a stack of leather-bound volumes pulled from the shelves. Cream with chocolate, yolks of eggs; the meat of the bird and a lover’s attentions. Instead of hoarding coals in a brazier and poking the ashes on a frigid morning, as the goose-girl had once done, she enjoyed fires laid by a maid (Léonie). All of it an extravagant taste of what had, in sixteen years of living, been skimmed off the top, plucked and gathered, measured and weighed; priced and packed and sold off down to the bones and renderings. My new life fit like a tailored bodice, a dressmaker’s creation tossed my way after the original wearer had cast it off. Indeed, there were corsets dug out of the chests and armoires; petticoats, bonnets, and stockings; past-fashion dresses belonging to absent relatives. In short order I learned to delight in foie d’oie rather than sell it; and soon greeted the rural folk at the Saturday market, the flower girl and the bread man, and chattered of our domestic affairs to Léonie, who uttered only murmurs of assent.

The Unruly Passions of Eugenie R.

The Unruly Passions of Eugenie R.