- Home

- Carole DeSanti

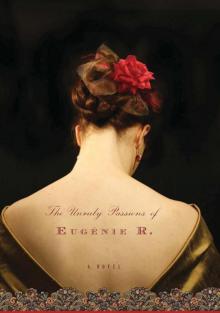

The Unruly Passions of Eugenie R. Page 5

The Unruly Passions of Eugenie R. Read online

Page 5

Tillac’s makeshift duck-and-goose market had been set up amid cooking pots, straw beds, piles of bandages, and the Nérac refugees. The traveler, come to buy the fowl in a lot and ship them north under arms, had set up his ledger and fine-nibbed pens; his Paris ink and his weighing scale with brass weights—and when he smiled, he cut through Tillac’s gloomy skies.

“My aunt’s birds have been fed with corn mixed with lavender,” I said in French, as my aunt’s interpreter. She had had slaughtered one of her beloveds and extracted the liver, pale and trembling, a glistening fatted treasure. Simmered it over a small fire with a bit of Armagnac. I bore it across the square in a clay bowl.

This traveler had never weighed a goose in his life, despite all his fancy accoutrements; nor had he any instinct to judge the prize inside. Sometimes the smallest and least likely revealed a liver that would save the winter. Until those feathered bellies were slit open, though, you could only guess whether the harvest would be thick or thin; the stones in the scale pan few or plenty. This stranger, bringing with him the heady perfume of cities, was just a messenger; what he knew about fattened livers was limited to what they would fetch in Paris. His errand was to buy them for less.

“Walk with me,” he said. He was a pillar, a birch; white as salt, supple in the buffeting winds. “Come and see where I’m keeping myself.” Everyone knew that the stranger had declined our simple village hospitality—though after the fires, it was scarcely that—to make camp in the chateau outside Tillac’s walls. An old place, with its windows boarded and nailed shut, its lands leased out.

The sky turned from pink-streaked to lavender; then violet, then indigo. Gray to black; then stars. Bats flittered, tree frogs chirruped. The scent of smoke still lingered in the air. We passed the black-haired boy and I experienced a small, ignoble flicker of triumph. My sabots felt their way along the familiar ruts of the path; lights from a farmhouse flickered in the near distance. Heart in my mouth; battering against my ribs. Fabric of my dress pulling tight, the bodice too small—it was a girl’s, and unfit for me now. The wind gusted in small bursts, carrying a cuckoo’s call, the sound of laughter, a voice from somewhere else. Louder—as Gers winds go—setting up a roar in the trees, storming up and falling back. On summer days it blew away the flies and bees and beetles; and when it died, the insects buzzed again in your ears and resumed their lazy circles. Stephan was my storm, my wind gusting up on a still night.

My neighbors, tongue-tied and timid, their patois not understood, were suspicious of him, and so my role in the business became that of an interlocutress. For the moment, I was flush with youth and eloquence—the former mayor’s eldest making good on her father’s promise; Berthe’s daughter with French on her tongue, able to guess at what this stranger didn’t know. A girl who had risen beyond gossip and a black-haired boy.

“Walk with me,” he said, amid the ink pots and goose feathers and clay pots and spoons; his fine coat splotched with goose fat. He stepped past the sooty rags, the piles of straw. His nails were smooth manicured ovals, mine ragged-edged and dirty when he took my hand in his and turned it palm up . . . “Travels, I think. Broken hearts. Not a destiny of the goose yard, I don’t believe . . .”

“And what does yours say?” I asked. A wild, ticklish, intoxicating laugh bubbled up and the seething whirl began; soon we were both choking with laughter, giggling and rolling in the pine needles and dust. Little bits of quartz from the soil jabbed into my back through my thin dress and, breathless, we rolled apart. His knee, bony and hard, could split me; his body arc and cover; faces flushed—lips that just brushed; scalding, ticklish, unbearable . . .

“Mine is a palm of narrow escapes.”

In the evenings, at my father’s table, I counted out the money, and my neighbors were shy with gratitude—though later, I believe, they told the story a different way. Mornings, I threw open the shutters and the scent that came across the Pyrenees was rich, fragrant with loam, perfumed with mysterious currents. And something in me had wakened and was rising fast, an errant planet in the autumn sky, past the tears and scraping of Papa’s gravestone and my mother’s rancid, bewildering scent, eau de vie and fury and perfume. It was a touch on my temple; an invisible kiss—some ghost of my life-to-be; a wild, aching, deep-abiding yearning.

“Come with me . . .”

The village square was silent for once, its familiar bustle quelled in the darkness before dawn as I hurried across, passing through the gate and the Tillac walls. Our mule stood ready, cases already strapped to his flanks. I climbed up and wrapped my arms around Stephan’s waist.

We rode past the forest edge, the stand of pines, branches heavy-boughed and thick-needled. An hour’s journey out, nearer the fires; the trees were blackened spires, rising jagged against a bruised sky. I tightened my arms; inhaled the scorched, befouled air.

Beyond the boundary of Gers province we dropped into the mists of the Lot Valley, where the morning cool turned sunny as midsummer by noon; rows of vines sweltered in the sun, and old men weighed bunches of grapes in their palms as they glanced at the sky. We changed our mule for a horse at Quercy and wandered in the market, where the summer peppers and fruits and salad greens were passing into a fall harvest of orange pumpkins, mushrooms, and beans; figs and braids of lavender-colored garlic. We stuffed ourselves with walnuts and later fell into a town banquet, a harvest celebration with a sheep roasting on a spit and small birds six to a stick, so you crunched down their tiny bones. We had plenty of wine and then a bed (or rather, two beds) at a whitewashed cottage that was a roadside inn. We were shy with each other; Stephan took my hand, so softly. Soon after that we were on a better road, a strange one; and the beats of the hooves made me sleepy, child that I was—but not for long.

We followed the flocks in the carts as far as Cahors, a two-day journey, and by then they were just birds in crates—not my aunt’s fine-plumed flock that I had hand-fed, nor the Widow Nadaud’s or those of two-fingered Stanis. Their marks of distinction blended amid the rough-and-tumble negotiation that was the weighing and selling of them.

After that first hurried leg, we took the railroad spur from Agen, and Gascony gave itself up to territory unknown. At Limoges we boarded a coach, crossing the Vienne River to approach the ancient city at night, when the sky was red from the glow of the porcelain ovens my father had told me about. We did not stop there, but carried on by railway. Second class; Stephan’s boot heels resting on a trunk as he told me about his family’s chase of fortune and misfortune; speculations good and bad; tales of women and roulette and cinnamon and coffee; defections to the Americas and some recent luck under the empire. My own stories seemed small by comparison, but we had a common bond: a kinship with the defiant of our clans. We had only kissed, but already we traveled as one, as though we had done so for lifetimes. I did not ask myself what I was doing. I simply knew.

From the Tours platform we took a conveyance pulled by horse. It was past midnight and inky black when we arrived, the two of us creased and grainy-eyed, identically rumpled, like stained laundry rocked along in a cart. Bare curved outline of a drive; crunch of wheels on stone, an expanse of velvety blackness beyond . . . “La Vrillette. The roof is falling in, the gardens overgrown, the gas is off, and the help has left, save a single girl. We are always in need of golden eggs in this family!”

Tawny owls nested on the ledges and in the attics, he told me, and what was left in the cellar was vine rot. As for the books, they were soon to be packed up and sold by the kilogram to an empire businessman who wanted to flaunt a library of old leather spines.

A jolt, and our movement ceased; the scent of late roses swelling into the closed warmth of the carriage. The night air smelled like mown hay, flowers, and rushing water all mingled together.

Stephan levered his boot against the door; gravel crunched as he stepped down.

In the front hall, he fumbled for the gas lamps, cursed and plunged through the darkness, then returned with a dining-table candelabra.

The chateau smelled of old silk and cork and wood, dusty velvet and polish; the air felt thick with ghosts. It was not quite a ruin; a fire had been laid in the bedchamber hearth and cast a flickering glow. In front of it stood an enormous tall-sided vessel, long and slipper-shaped, with a brazier at one end—a boat like that would soon sink, for it stood filled with water. Steam rose from the surface like fog over fields. I dipped in my hand, swirled my fingers through the silky warmth. What curious thing was this, and what absent soul had set the fire, carried enough water up a dark stair to float a small ship? Such bathing as I had ever known was a quick summer dousing in the river, or done quickly with a bristled brush and cold water in a trough, swiping beneath my chemise.

My traveling companion had shed his clothes and wrapped himself in a robe the color of wine, as familiar to him as my old goose-dress was to me. He shrugged it off in an easy movement, its folds puddling to the floor. A precarious laugh bubbled up in my throat—alarm, excitement, giddy disbelief. I dared not look, but did see in the shadows a lean and muscled whiteness there; then dark . . . He laughed and stepped over the tub’s edge. I knew then, but not before, that I was to drown.

Oh—my arms around his waist on horseback, so close. And on board the coach, inside a locked box that smelled of cologne and leather and horsehair.

“Climb in,” he said.

I inhaled the water’s wild perfume; sucked in my breath and stepped over. My chemise floated up (pantaloons were unknown to me then), and the water went in up to my calves, knees, thighs—then tickling warmth reached all the way inside me and the careening laugh came again. Stephan stood, firm as a flagpole, raining droplets of bath water. I screwed my eyes tight and plunged. (Allumette—bistoquette—colonne—goujon! A match, a cue, a pillar, a pin, a worm, a wooden leg—street argot that I had yet to learn. How did I know there were so many of them in the world—male members—and how they liked to behave?)

“Lift your arms—you’re not bathing in your chemise.” Stephan turned me and undid my laces, plundered the soggy garment. Candlelight flickered over my flesh, and I gasped and pulled up my knees. Some girls my age had never seen their own navel, but I was not one of those. Still, I had to gasp for breath in these unfamiliar waters. My breasts floated, rosy with the warmth. Stephan reached around me and cupped a palm around each, softly pulling me to him; both of us awkward; he was not as sure as he seemed. I might have shivered and drawn away, but the warmth pulled like a string from the nether regions to my heart, and I leaned back, and rested.

“You’ve brought along half the mud clods of Gascony, I see,” he murmured. Then with a cloth like a lion’s rough tongue he scrubbed my back and belly. His palms, with the cloth, followed the curves of my body—breasts, waist, softness of belly . . . lips, then—warm and steamy, traveled where hands had never been, turning me at last toward his mouth.

“I’m hungry! Is there anything to eat?”

“Foie d’oie from your village and some very old champagne. Not a crumb of anything else until tomorrow, when we can send Léonie to market.” He rose and stepped out of the bath, lifted me out in turn; settled us both on rugs in front of the fire. Lips buried in my neck; damp curls twisted between my fingers; we touched, kissed, leaned into each other for a very long time until our skin was warm and moist and waiting. The dark posts on each corner of the bed spiked up like trees and the filmy bed curtains surrounded us like fog. One could get lost in a bed like that, or fall from the height.

“You’ll stay with me, then, little goose?”

What else, where else—in the world?

We broke into our stock of foie d’oie, what Stephan had held back from the shipment. The rosy brown bloc was flecked with gold, nearly melting in the warmth. Stephan cut into it with a penknife, raised the blade to my lips, but teasingly, pulling it a little distance away as though it might scald.

I took the blade from his hand and licked it, allowing the rosy morsel to grow moist on my tongue. The stuff tasted like salt tears, like the dusky flavor of rain on earth, or morning light slanting, dustily, through the forest. Sun on the fields, purple clouds over the Pyrenees. Something so terrible and familiar like my own bones and skin, the milk from my own breast—the stuff that made me, had made us all, in that rough corner of the world. I tasted, and tasted again, tears rising. I had hardly ever tasted it. He took the knife and dropped it to the floor, moving his body closer, seeking my mouth with his.

“The candles are burning, we mustn’t fall asleep”—I slipped from bed to blow on the tapers, then licked my fingertips and extinguished an orange-glowing wick. The taste of smoke and tallow on my tongue, as I wet my fingers to put out each tip, joining the bouquet of salt and rain and goose fat.

“Don’t worry so, come—”

We slipped between linens softer than spring grass, the heaven of our bodies pressed together: musk, licking flames, tangled sheets. Made love half-dreaming amid the damp linens until I fell into the void between flesh and nothingness, a refuge of sweat and perfume, where the certainty of flesh answered a surge of breath and blood and heart. It was a shimmering field, a breeze rippling across golden stalks.

And so that night I began to shed, hardly knowing it, the fur-matted, pond-bathed, forest-floor earthy roughness in which I had lived all my life. The old things I’d thrown off were like animal skins, dark and coarse, thrust down in a corner; a gentle humid ferment of the fields. While below, more deeply, but sunlike too; a pulsing arose, sure and steady, pressing from within . . . A window flung open; perfume of late summer roses, the last blooms of the year. Beneath him, I burst like a September rain cloud.

The pool, the trees, and the cold, voluptuous marble of the Luxembourg—it was all as it had been moments before. Too chilly now, too dark; time to go. A turning, then; a quickening deep inside me. Not hunger . . . not fear or cold, but something warm, fluttering, tingling, a touch like a sigh. Feathery, winging pulse.

***

Back at the Tivoli, no Stephan and no word of him, not that day or the next, nor the one after that. No word . . . When did I realize that there would never be a letter? That my erstwhile lover would not gallop through the Passage, or alight from a cab, nor would any of the other hundred imagined scenarios unfold?

The fairy eye has closed, my aunt used to say, when the forest fountains ceased granting our wishes. When luck ran out, or went rotten. There was a familiarity to it, this sense of loss. I searched my memory for omens of betrayal missed, ignored, shoved aside by an urgent heart, but the candles guttered out before I found any answers.

And in some sense, it did not matter, the whys and hows of it. But of course, love does not believe or understand that; love simply weeps; it is bereft. A deep current of movement, and from below, from some uncertain interior part of me, rose a question, an unsteadiness. For the barest moment, the wisp of a desire to reverse the course of events, those of the present moment but perhaps others as well; events from long ago. A crumbling wall, the music of glass shattering, falling onto a stone floor in a million tiny fragments. The tearing of old silk, blue and ivory; patterned crystal; the beating wings of a large bird; a man’s body stretched full upon mine, his lips on my breast; a caress, melting away. Such a long road. So tired. Then uncertainty, and I fell a long, dark way.

Above the rooftops, the air was thin. Another day, one more sitting. One in which the coals that offered the atelier scant warmth burned down more than they were lit; and Chasseloup stared out at the buttes and smoked, a scarf wrapped round his neck. The studio’s expansiveness had narrowed to a foggy, helpless anxiety; a state of arrest. From my position, standing on the wooden slats, I watched the progress of the day’s light: dawn slowly grazing the wide surrounding sky, clouds wisping past windows. In some distant part of me, a bell clanged an alarmed tocsin, and yet I did not move.

Chasseloup accused me of standing as though all of my blood had drained from my veins. No position pleased him. “What do you think it is, this game, to work when you feel l

ike it?” He retreated to the windows. I wrapped myself in a dusty length of cashmere from the rental rack and sat down on the box.

He rolled another cigarette, the twentieth of the day. Stared out through the north exposure, toward Montmartre, invisible behind the flat, sleeting sky. He flexed his fingers and sighed. “I’m sorry. It’s not your fault.”

I began to cry. Chasseloup swore at the falling sleet.

On the easel was a line, rough and dark, but graceful. The contour of a shoulder, stretch of leg, curve at the waist. A girl half-turned, looking over her shoulder. Brief reprieve; shaft of light in the dark tunnel of self-recrimination.

“That is a good line,” I said, wiping my eyes with a handkerchief from the bins. “Berthe—my mother—taught me a strong line from a weak one.”

Chasseloup flipped through the pages on the easel. He shook his head. “She studied?”

Tears, and the ghost of an emotion tightened my throat.

“Her teacher was an old painter. Very old.” I smiled through my tears. “He hated Paris; he also thought there were too many railways here.” Pierre’s smoke curled upward; his eyelashes were so long, they lay against the curve of his cheek like a child’s. That I was his present cure, like wormwood, and he mine, had pulled us together through the hours.

“You must be cold,” he murmured. “Dress if you’d like. I am sorry to keep you.” He let out a breath and leaned back. He was tired. More tired, today, than I. It would not be so difficult to slip my arms around his shoulders and feel his warmth; be of comfort if not of use. I drew in a breath.

The Unruly Passions of Eugenie R.

The Unruly Passions of Eugenie R.